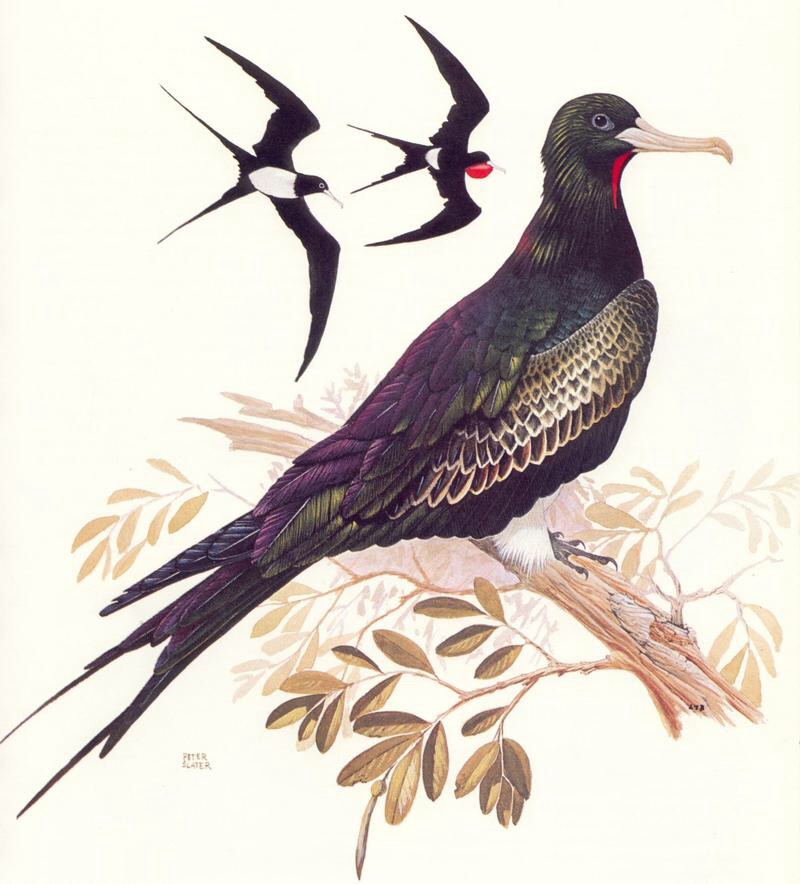

The Christmas Island frigatebird (Fregata andrewsi) has a small declining population which breeds within on just one small island. Allrhough the birds leave the breeding grounds and disperse over a large part of the Indian Ocean, it is not known to breed anywhere else. The Christmas Island Frigatebird is the rarest of the five species of the family Fregatidae. It is one of three frigatebird species which breed on Christmas Island. The Greater Frigatebird (F. minor) is far more common on Christmas Island and breeding is not restricted to the Island. The Lesser Frigatebird (F. ariel) was only recently discovered nesting on the island. In 2014 it was considered common on the Island with an estimated 1200 breeding pairs, while globally it is considered Critically Endangered.

Large, black, fork-tailed seabird with a conspicuous white belly in flight, also a pale bar on upperwings. The Adult male has red throat pouch and a long, dark grey, hooked bill. Adult female has black head and throat, a white collar, pink bill and red orbital ring.

The Fregatidae family of birds have the largest wingspan to body weight ratio in the world, which means it can stay air bound for more than a week at a time without rest. Another remarkable trait is its ability to perform kleptoparasitism, in other words, stealing food from other birds, usually in flight.

Breeding and non-breeding birds have been recorded foraging at low densities in the Indo-Malay Archipelago over the Sunda Islands to the South China Sea, the Andaman Sea, the Sulu Sea, off south-west Sulawesi, and in the Gulf of Thailand commuting directly over Java. When not breeding the species ranges widely across the seas of South-East Asia to Indochina and south to northern Australia.

It nests in tall forest trees. It is only capable of raising a maximum of one fledgling every two years. It forages for flying fish, squid and other marine creatures. Most food is captured by plucking it from the sea surface while on the wing, but it is also an accomplished aerial kleptoparasite. Evidence suggests that breeding birds frequently forage hundreds or even thousands of kilometres from the colony. It was first described as a separate species by Mathews in 1913.

In the Australian Avian Record (1913), G. M. Mathews wrote:

“The larger Christmas Island, Indian Ocean, bird identified by Sharpe as F. aquila is a very distinct species, characterised by the male having the abdomen white and the female being all white underneath from the lower throat to the vent. It is also quite a large bird, the largest female giving the bill 136 mm. and the wing 635 mm.

It gives me great pleasure to call this species “Fregata andrewsi”, sp. n., as it was due to Dr. C. W. Andrews’ gift that this investigation proved so interesting. Fregata ariel is differentiated, as is pointed out in the Catalogue of Birds in the British Museum, by the male having a white patch on the flanks.

It has not such a wide range as Fregata minor, but may even be more local, for one of the results of my researches is the proof that Fregata is practically a sedentary genus.”

Charles Andrews in A monograph of Christmas Island (1900) wrote this:

“At present Frigate-birds are one of the chief articles of food of the inhabitants of Christmas Island, and they are very good indeed. The usual way of obtaining them is for a man to climb into the topmost branches of a high tree near the coast, armed with a pole eight or ten feet long and a red handkerchief. The latter he waves about, at the same time yelling as loudly as possible. The birds attracted by the noise and the red colour swoop round in large numbers, when they are knocked down with the long pole. In this way sufiicient birds to supply the small colony with food can usually be obtained in an hour or two; occasionally, however, in unfavourable states of the wind, they are difficult to procure.”

Pearson in his birds of Christmas Island (1965) wrote:

“I believe Christmas Island is the only known breeding place of this species. Chasen found it plentiful in the region of the Anamba and Natuna islands in 1925 which suggested that it bred there but no proof of nesting was found. These islands lie between the Malay Peninsula and Borneo, in the South China Sea. It is a large frigate bird with distinctive markings. Gibson-Hill estimated the numbers as 1000-1500 pairs and again I am unable to say whether there are more or less than this at present, though it seems that the numbers of the two species of frigate bird are now about the same. I suspect that it is the Christmas Island species that has increased.”

First some interesting 19th century science directed to this bird, based on its kleptoparasitic habits. The year is 1880, the writer Joseph Green in Ocean Birds. Mister Green is convinced that the Frigate-bird might be in danger of extinction because it doesn’t use its feet to hunt. The feet have therefore detoriorated and, in the near futurethe frigate bird, will not be able to catch fish on its own. The reason is that the species steals its food from others and does not use its feet. Because the stealing of food is not liked by other species they will be fighting back or even support eachother in chasing this pirate away, rendering the frigate-bird helpless because it can not catch fish on its own.

Mister Green writes: With their small and partially webbed feet they are, as may be supposed, but poor swimmers, and, as their principal food is fish, they subsist to a great extent by plundering birds more skilful than themselves in the art of fishing. The principal victim to this aggressive policy is the Gannet, whose prey I have frequently seen appropriated by this handsome buccaneer. Ever on the look-out, wheeling and circling high aloft, if the Frigate-bird sees the successful dive of the Gannet than he swoops down in hot pursuit to gain possession of the prize. Generally the fish is meekly dropped, and being caught in mid-air by the pirate, is carried triumphantly away. That it has not the powers necessary for a pirate is equally clear, because even the small but sharp-billed Tern determined to fight it would defeat the toughest Frigate-bird that ever existed. A pirate’s life is proverbially a hard one, but terribly so must it be when the pirate is unfitted for the task. Summing up this well-known theory, Mr. Herbert Spencer says, “The dwindling of a little-exercised anatomical part has, by inheritance, been more and more marked in successive generations”.

Davenport Adams mentions a case where a Frigate-bird was pursuing a small Tern to take possession of its catch when a larger bird of a different species interfered and drove away the pirate, and then flew away on its own affairs, as if conscious of having performed a good deed. Thus it would seem that the bird-world resent this unnatural behaviour of the Frigate-bird.

Mister Green continues: “Buffon and many old authors depict the Frigate-bird with fully-webbed feet, so perhaps originally it was furnished to fish for its own livelihood. Like the Blind Crabs dwelling in the Caves of Kentucky, who have lost their eyes by disuse, so this bird may now, from the same reason, have lost the means of gaining an honest living. That the disastrous effects of disuse are hereditary there is no doubt.

It would appear that the Frigate-bird is a mild example of this theory, for certain it is that, though constituted to live on a fish diet, it has now no chance of catching fish in the still waters of the Tropics. We may therefore assume that the Frigate-bird will eventually lose its true hunting powers. But it is equally true that the effects of use are hereditary, it is to be hoped for its own sake, that a stronger and more efficient claws will make their appearance.

The Frigate-bird would appear to be in that dangerous transition stage that before has resulted in the extinction of the genus. This, however, seldom happens unless accompanied by some sudden change in the surroundings. One of the latest instances is the Dodo. Absolutely without enemies, it, from disuse, lost all powers of flight. Suddenly its habitations were inundated by man, and, without any time given to establish some other method of escaping, it was annihilated.”

A wonderful combination of pseudo science and misinterpretation of observation.

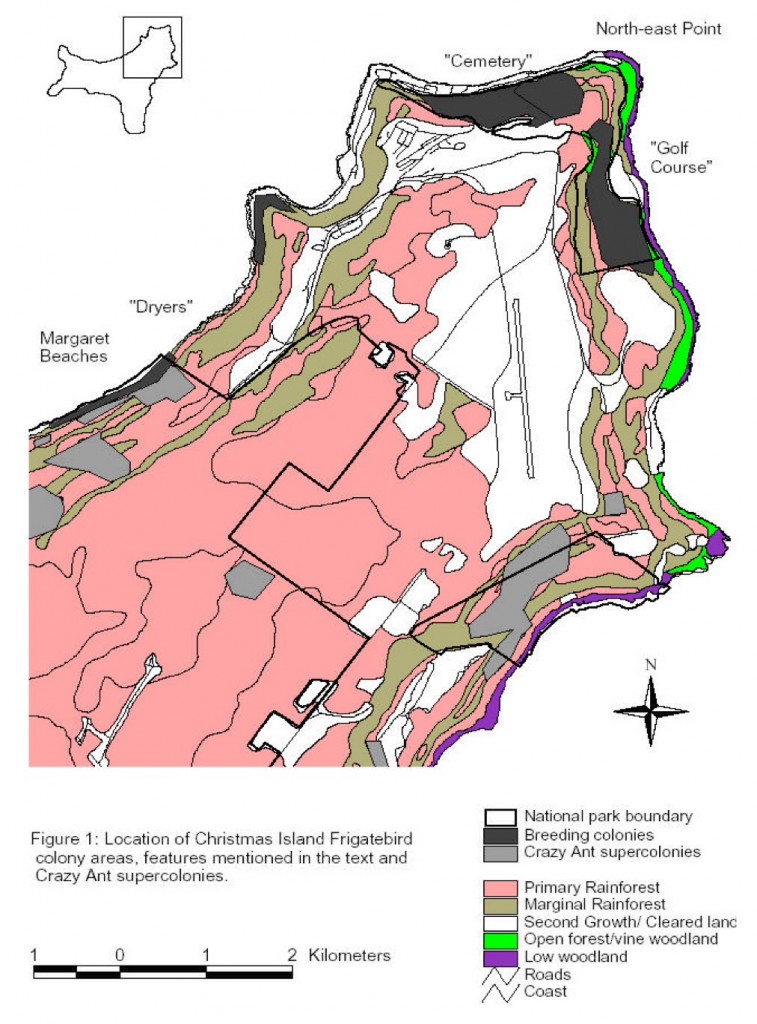

Historically, loss of breeding habitat has contributed the most to its decline. There was a large colony in Flying Fish Cove before human settlement. A large area of prime habitat was cleared at the Golf Course during World War II. The colony on the northern coast was large in 1967, affected by phosphate mining dust from 1971, sparsely populated by 1985, and abandoned by 2003. Harvesting Frigatebirds for food also had a severe impact, probably until the start of the eighties when this was no longer practised. Throughout the nineties a steady decline became apparent without obvious reasons on the Island. This suggested a threat during the non-breeding season when the birds disperse very widely.

The population probably declined by around 66% over the last three generations, mostly due to habitat loss, poisoned dust fallout from phosphate mining, water pollution, over-fishing and bycatch in fishing gear.

A specific threat to the Island, which has not yet affected the frigate-bird colonies is the invasive yellow crazy ant.

It, the exotic invasive yellow crazy ant (Anoplolepis gracilipes), arrived on Christmas Island more than 70 years ago, and is now widespread throughout the rainforest. These ants have the ability to form multi-queened super-colonies, in which the ants occur at very high densities. Supercolony formation has apparently been a relatively recent phenomenon; the first supercolony was discovered in 1989, with further dramatic increases in supercolony formation probably beginning around the mid-1990s. The density of ants is devastating for ground-dwelling animals in the forest, from i sects to mamnals. Also infested trees are effected in such a way, canopy growth is in danger. A control programme for this insect was initiated after 2000, including aerial baiting in 2002, and effectively eliminated the ant from 2,800 ha of forest (95% of its former extent) However, the ant population continued to increase, covering over 500 ha by 2006. Despite continued control efforts, ants remained persistent in 2009, but there is no evidence that they are negatively affecting frigatebird colonies.

We, at PoB, usually end with describing the conservation measurements taken by International organizations and local government. This time we are very sure this bird species wll survive in the long run. Probably their major threats will be thousands of miles from their breeding ground. The Island itself will remain to be a safe haven for the species. The Aussies will take care of that. So any more information on conservation look at birdlife.org the definitive source for saving bird species. Query google with this string: “fregata andrewsi” christmas filetype:pdf and you will find it all.